|

In june 2013 I published a blog post that contained a video focused on how to reduce world CO2 emissions from fossil fuels to zero by 2050. There has been a lot of publicity recently prompted by the release of the latest IPCC report on global warming. The IPCC keeps ratcheting up the pressure from the constantly accumulating evidence for the damage of climate change both today and projected forward into the increasingly near future. This focus at the end of another year seems a good time to revisit the primary motivation for Stratosolar. The central theme of Stratosolar is that the only viable solution to CO2 emissions reduction is clean energy that is a complete 100% replacement for fossil fuels that is significantly cheaper. Stratosolar is such a solution and current wind and solar are not.

Back in 2013 annual CO2 emissions were about 32 Gt/y. In 2018 they have increased to about 42 Gt/y, pretty much what was predicted by business as usual. There is a lot of publicity around wind and solar, but as yet they clearly have had little effect on CO2 emissions as we continue to accelerate our march towards climate armageddon. The 2013 video sets a goal of roughly 1 TWy average yearly reduction in fossil fuels to get to zero CO2 emissions between 2020 and 2050. That is still the goal but ramping production of sufficient replacement technology by 2020 is not realistic. To meet the 2050 goal and keep temperature rise below 1.5 to 2 degrees C will need a more aggressive ramp the later we start. Despite an increasing acceptance of the reality of climate change, the cost, complexity and uncertainty of clean energy solutions means adoption is low and driven mostly by government subsidies and mandates in rich developed countries. Most growth in CO2 emissions is in countries that are not the US, Europe and China. Paradoxically the US is the only player to actually reduce emissions. This has been due to cheap gas replacing coal. Wind and solar growth barely compensate for reduced nuclear. To get a perspective, todays approximately 100 GW/y of new nameplate solar is about 25GW/y of average generation. The goal is 1TW/y of average new generation. That's a factor of 40. If we split the demand evenly between wind and solar its about a factor of 20 each. That is just the generation. It does not count the storage and backup generation to achieve 100% renewable energy which are at least as much again. Currently we are spending about $250B on wind and solar. 40 times 250 is $10T/y. That cost is about 10 times current world investment in all energy infrastructure. Costs have to reduce by a factor of ten at least to fit current world energy budgets. That level of cost reduction in the relatively short time available is highly unlikely. Stratosolar eliminates the backup costs and reduces the generation cost by more than three on average, making costs within a viable range with historic cost reduction. 2TW/y of new Stratosolar at $0.75/W is $1.5T/y which is economically compatible with current levels of investment. As the IPCC shows, we are not on a path to success and time is running out It's time to evaluate what are seen as risky alternatives like Stratosolar. By Edmund Kelly

Comments

PV is not a free market. It is dominated by China and the peculiarities of the Chinese economy. China is both the largest manufacturer and the largest consumer of PV. This has all occurred extremely rapidly over about the last five years. 2017 appears to potentially be a year of reckoning for PV, as this blog article neatly summarizes. The total historical PV cumulative installed capacity is about 300GW, most of it installed over the last few years. 2016 Installed capacity alone was about 70GW, with about 30GW of that in China. US installed a record 12GW in 2016, driven by the potential expiration of subsidy incentives. Most projections have 2017 world PV installations falling well below the 2016 70GW due to reductions in China and the US, with no major new growth area to compensate.

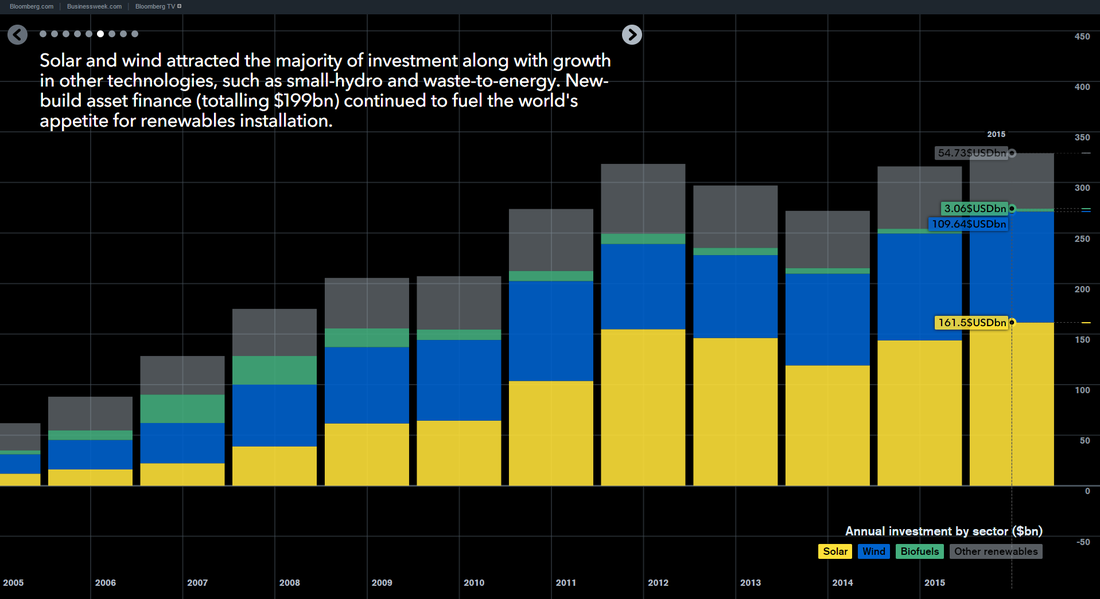

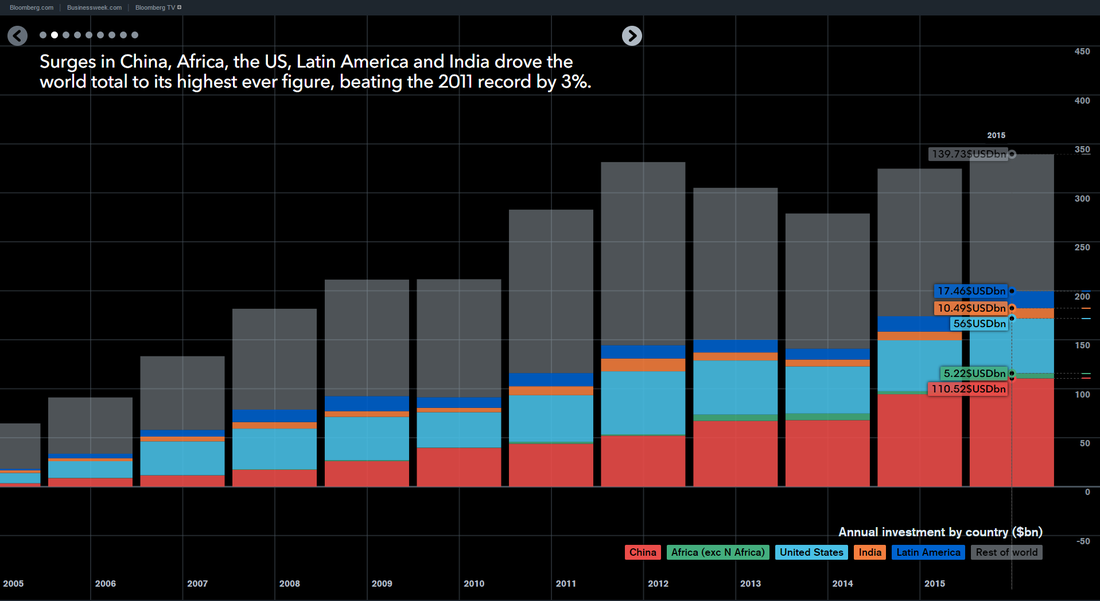

These reductions stem in part from the limited ability of electricity grids to absorb PV. The long-term limit is based on the capacity factor limit of grids to absorb intermittent sources. We are far from this limit, but short term constraints are showing up at very low levels of PV penetration. China’s current limit is the lack of long distance transmission capacity to take the power from the deserts in the west to the users in the east. As discussed in this blog post, California is hitting problems due to the inability of fossil generation to ramp up and down quickly enough to compensate for rapidly changing PV generation as the sun sets. Advocates for PV are focused on the falling cost of PV generation and seem to assume that once PV becomes the lowest cost of generation the world will magically switch to solar energy. The reality is far from this rosy scenario. The real cost of PV electricity will increasingly have to factor in the additional costs needed to incorporate it into the electricity supply system. California is showing the need for storage at very low levels of penetration and China is showing the need for long distance HV-transmission. Both technologies are expensive and in need of development, particularly electricity storage. They are both additions to the current grid and both exceed the cost of PV generation. Add to this the geographical variability of solar, particularly at northern latitudes and the economic case for solar to be a large scale, economically viable supplier of electricity is far in the future. StratoSolar is low cost generation with low cost, fast response storage built in and no need for long distance transmission. It has no daytime intermittency problem and it works well at northern latitudes. It needs relatively minor short term development to prove its viability. In contrast, the storage and HVDC transmission technologies needed to make ground PV viable are in many ways more speculative, unproven and longer term than StratoSolar. By Edmund Kelly Bloomberg came out with a 2015 update to their report on world investment in clean energy. Above are a couple of charts showing the overall investment by type and by region. Total investment rose slightly (3%) over 2014 to $328B of which $161.5B or 50% went to solar. The overall investment level has not changed significantly for the five years, 2011 to 2015. Over this period solar has stayed about the same percentage of clean energy investment. Annual solar capacity has grown from 25GW to over 50GW, so the average cost of solar has dropped significantly from about $6.40/W($161/25) to $3.20/W($161/50), moving solar closer to wind in cost. PV panel costs have not declined much over this period ( after a dramatic decline around 2011) so most of the solar cost reduction has been from the rest of the system. The rate of these system cost reductions is slowing. The overall world average cost covers a very wide range of systems, from high cost rooftops over $6.00/W to very large utility arrays at less than $1.50/W, along with large regional differences in labour and regulatory costs. As the regional market chart shows, there has been a significant change in where the investments are taking place over the five years. The two biggest trends were the decline of Europe and the rise of China. Without China’s decision to dramatically increase its clean energy investment in 2014 and 2015, the overall market would have declined every year from 2011. Despite dramatic reductions in price, investment in solar has hardly increased. This tells us that solar investment is not yet driven by market forces. The price will have to fall substantially from current levels for solar to become market competitive. Overall the charts present a picture of a stagnant clean energy market. Given the need for government support to maintain the market, the world economic slowdown does not bode well for growth in the clean energy market, particularly in China. Despite its greater than $300B/y size, the current clean energy market is not reducing CO2 emissions by any noticeable amount. Based on these charts it is not on a path to do any better. There is a need for a change. StratoSolar makes today's PV a practical replacement for fossil fuels. Its an incremental improvement of PV, not a dramatic revolutionary new technology. It is easy, quick and cheap to prove its viability. The path we are on is clearly not working. It is worth giving StratoSolar a try. By Edmund Kelly The attached white paper is a more comprehensive look at the impact of higher energy costs on reducing GDP growth. This tells us two things. First, we are in serious economic trouble already with a low and declining rate of economic growth from the continually increasing cost of fossil fuels. Second, replacing fossil fuels with more expensive alternative energy sources will only make the problem worse. So far, wind and solar have been a relatively small economic factor, but growth to a level where they can contribute to a significant reduction in CO2 emissions would quickly get us into economic decline, and the political unrest that comes with economic decline. StratoSolar's lower cost of energy production than fossil fuels can reverse the current decline in the rate of economic growth by making energy cheaper on a continuing basis. By Edmund Kelly

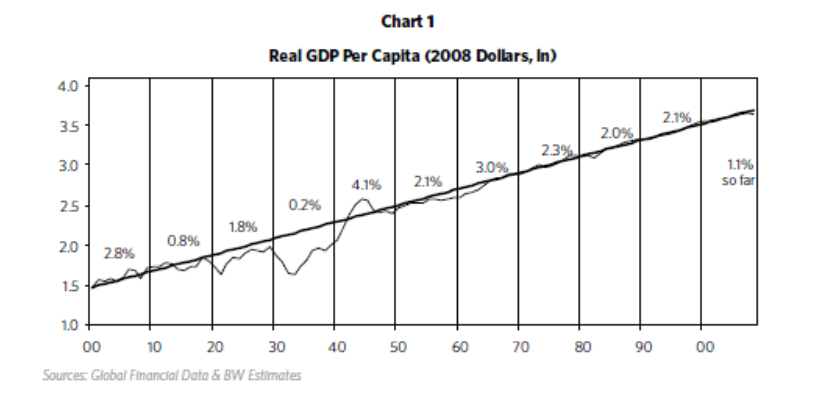

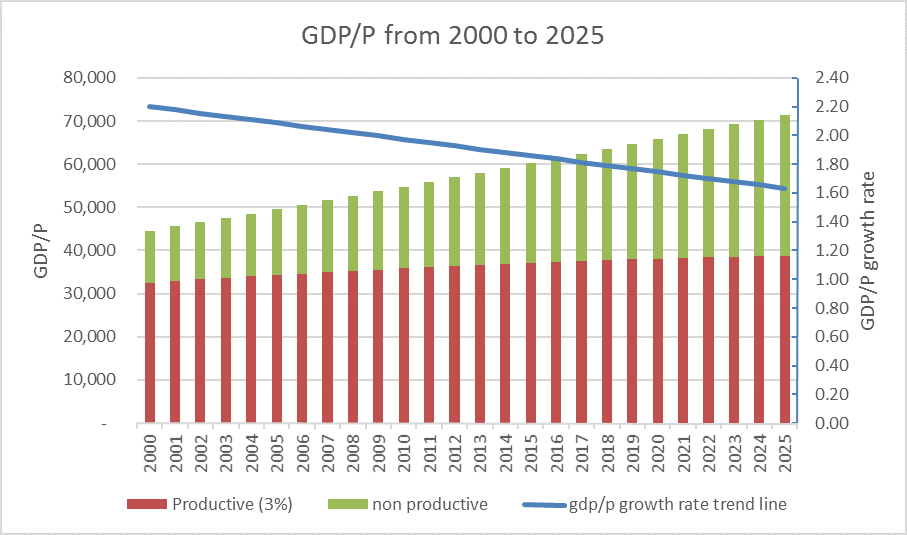

An argument against large scale deployment of alternative energy is the negative impact of the higher cost on gdp growth. The following is an attempt to quantify this effect based on the increasing cost of energy since around 1970. The modern world is based on sustained economic growth. As the chart below shows, US real gdp per capita has maintained an overall 2% per annum growth rate through depression, recessions and two world wars. This has been possible because of technological advances increasing the productivity of all economic sectors. Since around 1970, the cost of producing energy has steadily risen. Initially this was driven by the increasing cost of oil production, and more recently the cost of expensive alternative energy production has also become a significant factor. Energy is a significant part of gdp, so its share growing from around 5% to around 10% of gdp should clearly have been a drag on the growth rate of gdp, reducing it from its long term 2% per annum historical trend. When we examine US GDP growth rate data for various periods from 1960 to today, regardless of the period chosen it is apparent that growth rates have been on a steadily declining trend. The straight line in the graph below shows a snapshot of the actual downward trend from 2000 to 2015 projected forward to 2025. The colored bars also illustrate a simple model that assumes the economy has two sectors. One sector has a high productivity growth rate of 3% and the other sector is stalled out with 0% productivity growth rate. To make the numbers fit the data we need to start with the non productive sector at 25% of GDP. This produces a breakdown like that shown, with the non productive sector continually increasing as the overall growth rate declines. These numbers imply that a larger sector of the economy than just energy is contributing to the recent decline in economic growth rate. Increased energy costs account for about a third of the decline by 2015. The other likely contributors to low growth rate are substantial parts of the financial sector, health care and education. This reduced rate of overall economic growth is causing severe economic problems already, with income inequality and stagnant wages. The problems will only get worse if the growth rate continues on its current downward trend. This illustrates that economic growth is a sensitive thing that cannot survive a large part of the economy becoming less productive. This should make it clear that a competitive, lower cost source of clean energy is a necessary condition for an energy transition that does not destroy economic growth. Current wind and solar are currently several times the needed lower cost and are reducing in cost at too low a rate to be an affordable solution for a long, long time. Other approaches like StratoSolar that can solve the problem without destroying the economy deserve some serious attention.

This white paper covers the topic of the reduction in economic growth caused by the increasing cost of energy.

By Edmund Kelly By Edmund Kelly

The rapid drop in PV panel prices in 2011 has led some optimists to predict continuing rapid price declines, particularly in the US. The triggering event in panel price decline was the drop in the cost of poly-silicon from over $100/kg to under $20/kg. This drop in price came as a result of investment in poly-silicon capacity which broke a cartel that had been keeping prices artificially high. This article by Matthias Grossmann describes the history in detail and focuses on the conditions necessary for renewed investment in poly-silicon production. He concludes that poly-silicon prices higher than the current $20/kg will be necessary to get investors on board. As supply is coming into balance with demand, that increased price is already happening, so investment in poly silicon production is likely to resume. All this means is that rapid PV panel price declines from current levels are not likely and current price levels will prevail for some time. Current overall capital costs for large utility arrays varies from about $1.50/W to $2.00/W depending on a variety of project specific details, like local labor rates, land and regulatory costs. Interestingly, if low cost financing is available and you have the high capacity factor of a desert, this capital cost level can produce electricity competitive with fossil fuels without subsidy, as is illustrated by this project in Dubai. However 100% project financing at 4% for 27 years is not yet the norm. For StratoSolar financing we assume a working cost of capital of 8.5% over 20 years which results in about $0.06/kWh for electricity. At 4% financing we would be under $0.03/kWh. That is so low a cost for electricity that it would be immediately disruptive in all markets and would drive very rapid growth in installed capacity. This would drive down costs which would further drive down the cost of electricity. If we can prove the viability of high altitude, buoyant, tethered, platforms, the foundations laid by PV growth and the continuing improvement in PV technology will enable spectacular rapid growth for StratoSolar systems worldwide. By Edmund Kelly

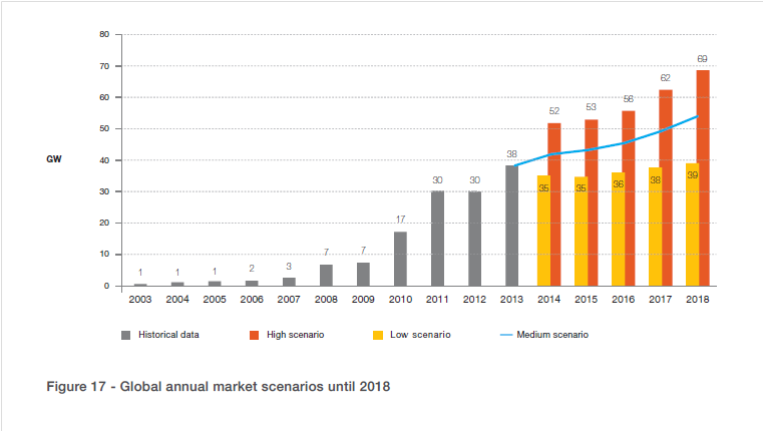

There was a recent article in IEEE Spectrum that explained why Google halted an energy research effort called RE<C (Renewable Energy less than Coal). It prompted this critical analysis by Joe Romm. Its rare to see this perspective on clean energy discussed in any detail, so I was pleasantly surprised to see two articles on this topic. Between them they explained two positions that have much in common but differ in important ways. The Google engineers discussed how they had started with the goal of renewable energy less than coal and after several years of effort came to the conclusion that current technologies were not going to achieve that goal. In large part this realization came from the understanding that the problem was far larger than they had initially understood. Google halted their efforts in 2011. Google invests heavily in alternative energy deployment and in its operations is very focused on reducing energy, so halting RE<C was in no way a vote against clean energy or dealing with climate change. Joe tried to paint the Goggle engineers as confused and misguided. Joe is a strong advocate for the status quo opinion on how to deal with climate change. Basically that position is; what we have with current wind and solar is good enough and what is needed is policy change, preferably a carbon tax. This tax will somehow magically cause fossil fuels to decline and alternative energy to prosper. Joe does not see RE<C as a necessary or desirable condition for dealing with climate change. At its core this is a view that politics can dominate the large scale economics of energy. When Joe discusses the problems with nuclear power he is happy to use the facts of nuclear costs to counter the optimistic promises of nuclear advocates. In contrast when Joe discusses energy policy he uses the optimistic promises of carbon taxes rather that the facts of decades of failure to get agreement on such policies and the overwhelming evidence that such policies are unlikely to ever be approved at a global level. On top of that there is no clear evidence that such taxes will have the desired consequences. Developing nations, where most new energy consumption is concentrated see higher cost energy as a threat to their development. The central debate is simple. Some (including Bill Gates) see RE<C as a necessary condition for the world to deal with climate change. This opinion is guided by the facts on the ground and the central importance of economics in decision making. Joe and the status quo clean energy consensus he represents see economics as secondary to policy, and believe that advocacy will achieve policy change and policy change will lead to the demise of fossil fuels and the rise of clean energy. StratoSolar is a solution to RE<C. As Joe makes clear, the clean energy status quo does not believe that such solutions can exist and that they are not necessary. Unfortunately this perspective is self fulfilling in ensuring no such solution sees the light of day. By Edmund Kelly This sixty page report EPIA Global Market Outlook for Photovoltaics 2014-2018 paints a pretty accurate picture of the recent history of the global PV market and has realistic projections for the near term. It has detailed information for each geography and market segment. The graph below from the report shows the near term overall world market projection with optimistic, pessimistic and realistic scenarios. The realistic middle scenario shows slow overall market growth, but no spectacular take off.

The conclusion of the report is a welcome return to reality about the future prospects for PV and a marked contrast to the over optimistic assessments that still seem to pervade the PV business. The central point of the conclusion is that “ The PV market remains in most countries a policy driven market, as shown by the significant market decreases in countries where harmful and retrospective political measures have been taken.” A policy driven market is a euphemism for a subsidy driven market. This lines up with my assessments of the prospects for PV business over the last several years as published in this blog. PV growing at this rate is fine for the PV business, but will not make PV a significant source of electricity anytime soon. It is not sufficient growth to drive costs down, so the business will need subsidy for the foreseeable future. The conclusion of the report backs this assessment as it clearly states that growth is dependent on “sustainable support schemes”. i.e. more subsidies. At some point those that promote current policies in the belief that they will reduce CO2 emissions have to stand back and make a realistic assessment of what they are accomplishing, or more accurately failing to accomplish. By putting all their eggs in the current wind and solar baskets, they are actually precluding investment in possibly better technologies. The psychology seems to be driven by a fear that admitting that current wind and solar are failing, will lead to nothing being done, and something is better than nothing. The reality is that investing only in failure guarantees failure. By Edmund Kelly If we focus on new electricity generation capacity worldwide a pattern emerges that somewhat explains the lack of progress on reducing CO2 emissions. New electricity generation investment is about $400B/y, $200B/y in wind and solar and $200B/y in coal, gas, nuclear and hydro. Another $300B/y is invested worldwide in electricity transmission and distribution.

Looking at how the investment is apportioned between countries, a convenient division is between OECD and non OECD. This is a pretty accurate division between developed nations and developing nations. Developed nations have a relatively low growth in overall electricity capacity, with most new generation replacing old generation. Developing nations are growing their overall electricity generation capacity at a rapid rate to balance their rapid GDP growth. Interestingly, from a dollar perspective OECD and non OECD spend about the same on wind and solar, about $100B/y. Developing nations spend most of the $200B/y that is spent on coal, gas, nuclear and hydro, over 66%. They also spend most of the investment for transmission and distribution, about 66% or $200B/y. Because of the rapid pace and large scale of development, developing countries follow a well proven path of investing in low risk, proven, safe, and cheap technologies. Developing countries account for the bulk of investment in electricity infrastructure: about $450B/y (200 T&D + 150 G + 100 A)of the $700B/y. (T&D is transmission and Distribution, G is conventional Generation and A is Alternative generation) All of the OECD invests about $250B/y (100T&D +50G + 100A). In the OECD, wind and solar investment exceeds other generation by a significant margin, but in the non OECD the ratio is reversed. We are at point where PV is still too expensive to compete without subsidies. So what do Europe and America do? Introduce tariffs to protect domestic producers from Chinese imports. This protection supports already inefficient subsidized industries. What is the incentive to reduce costs through innovation when profits are guaranteed and competition is blocked? PV at current price levels will not become a significant enough producer of energy to have any affect on reducing CO2 emissions. Perhaps rising PV prices will break the cycle of over optimism about PV and get some focus on investments that might lead to competitive, clean, sustainable sources of electricity. Investors in Solar projects in the US and Europe think it burnishes their image as responsible planet aware companies when all they are really doing is partaking in corporate welfare on a grand scale. Public funds are subsidizing half the costs of private PV investment and guaranteeing large profits. Their actions prop up inefficient PV industries who rely on subsidies and now protective tariffs. There is little incentive to lower cost to where the PV business can grow without subsidies and perhaps help reducing CO2 emissions. Solar investors are reinforcing the equivalent of fiddling while Rome burns. The developing world (non OECD) is on a path to a high energy future based on fossil fuels. It is simply the affordable path and as such the only viable path out of poverty. Most of the of the doubling of world energy consumption by 2050 is projected to come from the developing world, by which time it will consume more energy than the developed world.

The developed world (OECD) is already high energy and despite much weeping and gnashing of teeth, is projected to continue burning more fossil fuels at current rates into the foreseeable future. Interestingly, the world already spends about $200B/y on alternative energy generation, over half its $400B/y overall investment in new electricity generation. This is divided roughly equally between the OECD and non-OECD countries. This is an objective measure of the considerable amount the world is collectively currently willing and able to pay for fossil fuel free energy. Unfortunately this currently only buys about 17GW average generation, or about 1% of world electricity generation, or about 0.1% of world primary energy. This is insufficient to reduce CO2 emissions which are projected to rise every year into the foreseeable future. The level needed to be on a path to reduce CO2 emissions is 500GW to 1TW average new clean generation every year. This is twenty to fifty times current levels. This highlights the patently obvious but constantly ignored fundamental nature of the problem. To paraphrase James Carville “Its the economics, stupid.” This succinct phrase gets to the heart of political reality. No matter if the energy problem is seen as climate change, energy security, resource depletion or poverty, the real problem is the economics. Energy is just too big a part of the world economy for it not to be so. Significantly increasing the cost of energy by replacing fossil fuels with current high cost wind, solar and nuclear will never be politically acceptable. So we are at an impasse. The current technologies lead to policy proposals that are politically unacceptable and a very polarized debate that can never succeed in forming a consensus. The politically viable solution to this economic problem is new sources of clean sustainable energy at lower cost than fossil fuel energy. Unfortunately the current energy policy consensus is frozen like a deer in the headlights. The common wisdom is no such present or near future low cost technology exists and the need for immediate action means we should find ways to finance more of current high cost technologies. Unfortunately this policy approach violates the first law of politics and as such has failed and is doomed to continue to fail. Breaking the impasse needs fresh thinking to get more options on the table. The consensus that there is no possible low cost energy alternatives is a self fulfilling prophecy if it leads to no attempt to search for such solutions. Policy proposals tend to be broad and vague. Here is an explicit proposal that is not meant to compete with the status quo. Relative to world energy investment of about $1.6T/y, $10B/y seems an affordable amount to spend on energy R&D focused exclusively on high risk, clean electricity generation, power plant solutions. This is not basic research and it is not government R&D. A model is Space-X. Space-X is a private company focused on a product and works on fixed price contracts with fixed deliverables. Its like venture funding. Say The US, Europe, and China each established $3B/y venture funds to fund high risk energy development companies. By high risk, I mean high risk. Already, despite starvation levels of investment, some such companies exist. There are several fusion energy companies. There are several companies focused on sustainable fission of Thorium and U238. There are high altitude wind companies, wind on the ocean, solar in space, the desert, and the stratosphere. Funding these and others to start with would bring out a lot more. Companies would start at say $10M/y or more depending on their current stage of development. Funding would be for fixed deliverables and if on successful paths a few would get to say $500M/y, keeping the average at around 100 companies at $100M/y. This portfolio approach would lead to exploring many approaches and the probability of significant advances in less than five years. One significant success is all that is needed. Its not inconceivable that private equity would eventually join the party, and share the risks and rewards. By Edmund Kelly |

Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||

|

© 2024 StratoSolar Inc. All rights reserved.

|

Contact Us

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed